Hicks and the accident report agree that the wrong tool was used. “You have just put voltage potential on your entire car.” “It would be just like you taking your car battery and you touch a screwdriver to the positive terminal on the battery and you touch the frame of the car,” Hicks explained.

Hicks said the metal of the screwdriver contacted the positive side of the fuse and also the fuse’s grounded metal holder, causing a short circuit that sent electricity flowing to unintended places.

According to that story, it was merely the removal of the fuse with a screwdriver - not the insertion of the fuse - that caused the problem. Hicks arrived at the silo later and heard a simpler story from his team chief. Mountain Standard Time, “simultaneously with the making of this contact, a loud explosion occurred in the launch tube.” “At 1500 hours MST,” the report said, referencing 3 p.m. Still not certain he heard a click, he pulled the fuse out a third time and pushed it back into the holder again. But there was no click, so the airman repeated the procedure. The sound of a click indicated good contact with the holder. When the fuse was re-inserted, the report said, it was supposed to click. The report said the airman was “lacking a fuse puller,” so he used a screwdriver to pry the fuse from its clip. Though the launch tube was between them and the missile, the missile was not much more than an arm’s length away.Īccording to the Air Force report on the accident, one of the airmen removed a fuse as part of a check on a security alarm control box. The airmen worked in the roughly 5 feet of space between the steel launch tube and the equipment-room wall, among racks of electronics and surfaces painted mostly in pale, institutional green. Next, they climbed the ladder down to the equipment room, which encircled the upper part of the silo and missile like a doughnut.

Minuteman missile silo locations montana series#

Working in 24-degree conditions above ground, the airmen began a series of steps with special tools and combination locks that allowed them to open the massive vault door. The door concealed a 28-foot-deep shaft leading to the underground work area known as the equipment room. A couple of paces away from that was a circular, steel-and-concrete vault door, about the diameter of a large tractor tire. One of the structures was a 3 1/2-foot-thick, 90-ton slab that covered the missile and would have been blasted aside during a launch. Toward the south end were several low-slung tops of underground concrete structures. The unremarkable-looking place consisted mostly of a flat expanse of gravel. The rectangular, north-south aligned, 1-acre silo site was surrounded by a chain-link fence that was topped with strands of barbed wire.

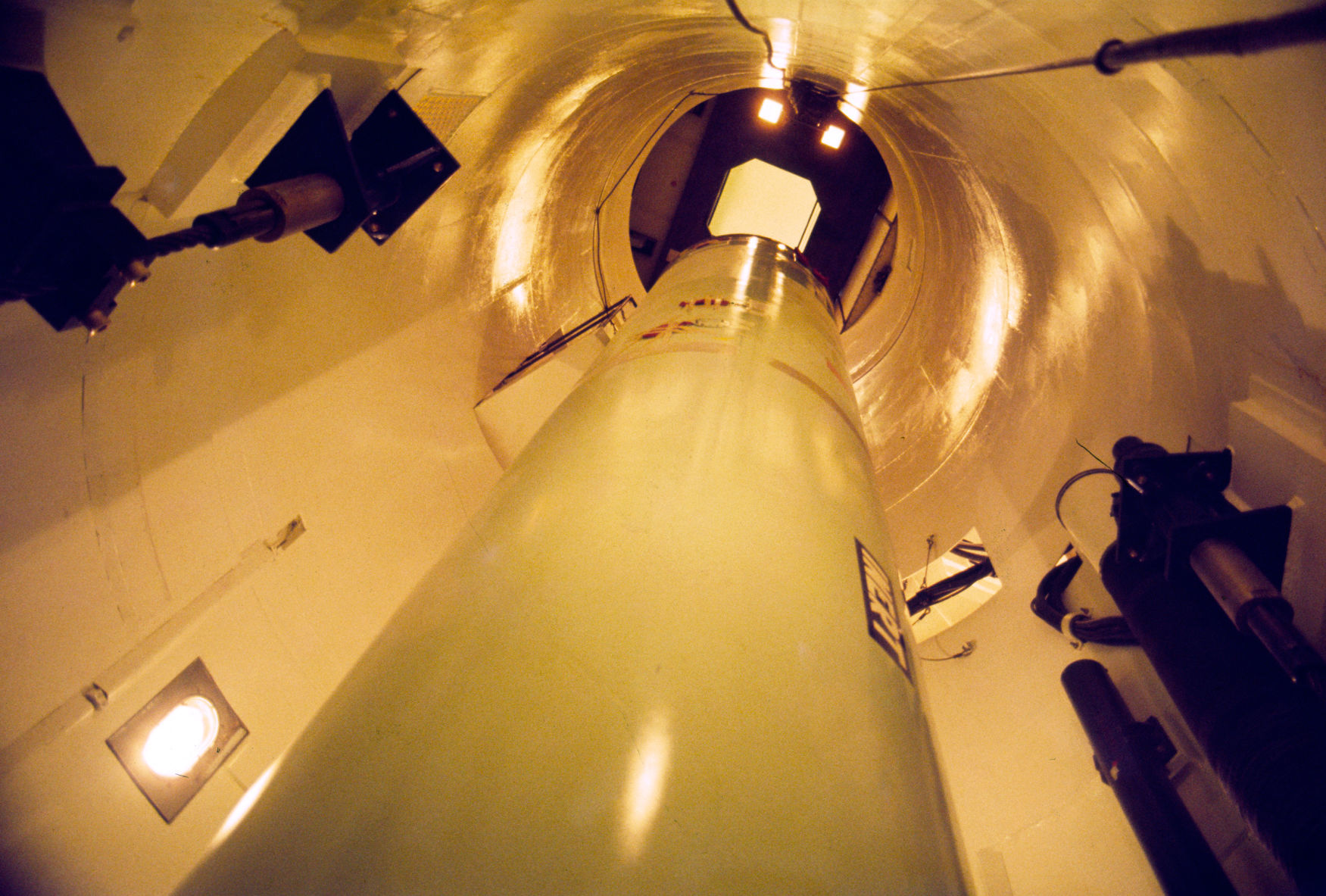

(Hannah Hunsinger/Rapid City Journal via AP) An explosion popped off the missile's cone -the part containing the thermonuclear warhead -and sent it on a 75-foot fall to the bottom of the 80-foot-deep silo. The silo looks much the same as a former silo near Vale that Hicks entered in December 1964 as part of the response to an accident. 27, 2017 photo, Bob Hicks looks at the unarmed Minuteman missile in the Delta-09 silo recently at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site near Wall, S.D.

One government agency reportedly estimated that the detonation of an early 1960s-era Minuteman warhead over Detroit would have caused 70 square miles of property destruction, 250,000 deaths and 500,000 injuries. The missiles were capable of traveling at a top speed of 15,000 miles per hour and could reach the Cold War enemy of the United States, the Soviet Union, within 30 minutes.Įach missile was tipped with a thermonuclear warhead that was many times more powerful than either of the two atomic bombs that the United States dropped on Japan during World War II. The original Minuteman missiles, called Minuteman I, were 56 feet tall and weighed 65,000 pounds when loaded with fuel. There were hundreds more silos in place or soon to be constructed in North Dakota, Missouri, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and Nebraska, eventually bringing the nation’s Minuteman fleet to a peak of 1,000. Lima-02 was one of 150 steel-and-concrete silos that had been planted underground and filled with Minuteman missiles during the previous several years in western South Dakota, where the missiles were scattered across 13,500 square miles. It was 60 miles northwest of Ellsworth Air Force Base and 3 miles southeast of the tiny community of Vale, on the plains outside the Black Hills. The trouble began earlier that day when two other airmen were sent to a silo named Lima-02.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)